Check out this concerning article on one of my favorite places to fish in the Tampa Bay

SHELL KEY — A few decades ago this uninhabited island at the edge of the Gulf of Mexico was little more than a small crescent of sand and mangroves with a tiny spit of land to its south.

Today the south Pinellas County barrier island known as Shell Key Preserve stretches 2.6 miles and occupies 1,800 acres of beach, mangroves, sea grass beds and sand flats.

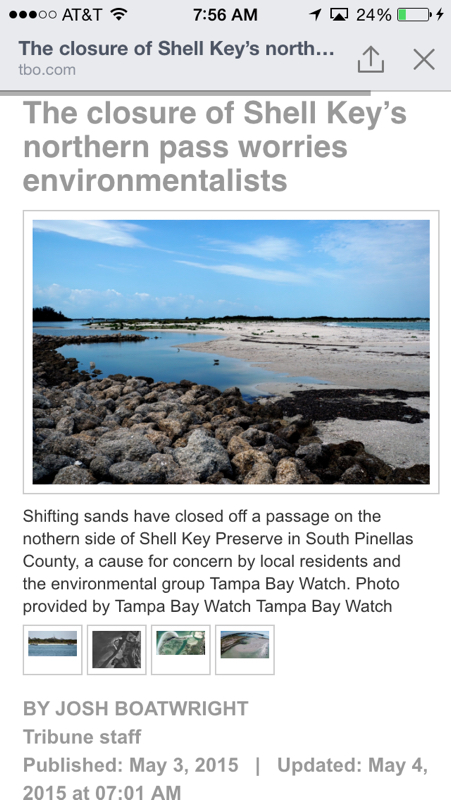

After years of storms, tides and even dredging to keep Shell Key separated from the community of Tierra Verde, a small channel on the island’s north side appears finally to have closed off, creating a sandy wall that seals the estuary on its back side from the Gulf.

This sort of thing can happen when man doesn’t interfere with the natural shifting of sands on these ever-changing coastal islands. But the speed with which Shell Key has transformed worries one of the area’s leading environmental groups, Tampa Bay Watch.

“This used to be a major pass, hundreds of yards across,” said Peter Clark, president of the organization headquartered nearby in Tierra Verde.

Now that the pass has closed, there’s no water washing back and forth from the Gulf into the shallow, sensitive habitat to the south — let alone access for boaters.

“It’s kind of like the bathtub effect: Water will slosh up and down the northern side of the preserve, but it can’t be exchanged with water from the Gulf or Tampa Bay. That water becomes stagnant; it becomes superheated, which can kill sea grass beds. It may also allow for larger algae blooms,” Clark said.

While county officials have yet to perform a comprehensive study of what’s happening at Shell Key, Clark has a theory about what has caused the particularly rapid accumulation of sand here: hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of sand pumped every few years onto the eroding beach just north of the preserve at Pass-A-Grille.

Beach nourishment has been rebuilding Pass-A-Grille Beach, at the southern end of St. Pete Beach, since the 1980s, a critical measure to protect the historic beach community from Gulf storm surge.

“A lot of the sand is probably moving its way south and that’s what’s been accumulating on Shell Key, making the barrier island much, much bigger and eventually clogging the pass and filling it in,” Clark said.

Near the mouth of Bunces Pass, a channel that separates Shell Key’s south end from Fort De Soto Park’s north beach, another large deposit of sand has formed in recent years, creating a huge offshore sandbar even as sections of the park itself have eroded severely.

Sand along Central Florida’s Gulf coast tends to shift over time from north to south, but Pinellas officials can’t say for sure whether all the sand that has ended up on Shell Key or off Fort De Soto’s shores has come from Pass-A-Grille.

When funding is available, the county’s Natural Resources Division plans to study both the Bunces Pass inlet and Pass-A-Grille Channel, which is just north of Shell Key, between Pass-A-Grille and Tierra Verde.

The goal is to assess the effect of these two channels on the long-term movement of sand in the immediate area and also to gauge why Shell Key has grown so much while parts of Fort De Soto have shrunk.

“That might give us some idea why that’s filling in and what might be the future of it,” said Andy Squires, the county’s manager of coastal and freshwater resources.

The county also has alerted the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, which manages beach nourishment projects, about people’s concerns about the Shell Key pass closure.

For the time being, though, it is unclear whether the change at Shell Key is simply a natural phenomenon.

Several efforts have been made in the past to keep a channel open between northern Clearwater Beach and undeveloped Caladesi Island State Park, an island about the same size as Shell Key, but natural forces keep closing it back up.

“That’s what these barrier islands do, they migrate. Shell Key was barely anything. That whole island in the last two decades has changed significantly and grown,” Squires said.

“There’s an evolution of these barrier islands.”

Local recreational boaters have seen that evolution happening from one year to the next along Pinellas County’s southern coastline.

“It ebbs and flows. A couple years ago there was a sandbar out in front of Shell Key. Now there’s a big sand bar to the west of Fort De Soto. It is constantly changing,” said Bill Knepper, a boater and resident of the nearby Vina Del Mar community.

He has seen large boats navigate Shell Key passage but, at other times, a jet ski hardly could squeeze through it.

While much of the change may be natural, Knepper said he does have concerns about the pass being stopped up.

“Once that water gets stagnant, then everything back there dies,” he said.

Tampa Bay Watch plans to ask the Pinellas County Commission to begin monitoring water quality in the Shell Key estuary to determine how detrimental the closure is to the environment there, Clark said.

In addition to stagnating water that could kill off sea grass beds, Clark also worries about raccoons, coyotes and other predators gaining access to the island to prey on nesting birds and their eggs.

The next time the Army Corps is scheduled to nourish Pass-A-Grille, Clark’s group will urge it to consider dredging sand from the north end of Shell Key and redistributing it at the beach.

A smaller-scale effort a few years ago to dredge the channel by private developers in Tierra Verde did little to deter the flow of sand.

Pinellas officials would have to seriously consider how much good dredging would do in the long run, says Paul Cozzie, director of the county’s parks and conservation resources department.

“The real question is how successful would any dredging be or is this something that’s going to have to be continually done and, in that case, who should be paying for it?” Cozzie said.

Dredging for beach nourishment projects is funded primarily with federal dollars combined with matching state and local money, but the Army Corps and contractors determine where sand will be collected.

The larger solution may prove complicated, especially on a natural preserve that is meant to remain untouched by human intervention, he said.

“Sand is going to go where it wants to go and it is a preserve, so we’re not going to use really any artificial means,” Cozzie said.

(727) 215-1277

Twitter: @JBoatwright

RSS Feed

RSS Feed